How one teacher developed buy-in and empathy in her students

When learning specialist Chelsea started planning for the first-year seminar she teaches, she started with what she calls “market research.” She talked to the students’ 8th grade teachers and asked what they were most concerned about for the students as they moved up to high school. It would be a big transition for this group in particular – they had gone through two years of COVID-19 disruptions and hadn’t had a normal school experience since the 5th or 6th grade. In addition to their academics, Chelsea wanted the seminar to focus on their social and emotional development.

“I heard across the board before I even had them that empathy is lacking in these kids,” Chelsea recalls. “So I was like, ok, I got this, I can do this.”

The first-year seminar is intended to help students embody the school’s core values: authenticity, respect, curiosity, kindness, and agency.

“I would come in super excited with these team building activities that we were going to do and it would just completely blow up in my face,” Chelsea says.

One lesson in particular – a cup challenge – did not go according to plan. Students are each given a piece of yarn that is attached to a rubber band. Using the yarn together, they need to pull the rubber band around a plastic cup and while still only holding the yarn, stack the cups to build a tower. While some students completed the task, others struggled. For Chelsea, it was the moment when she realized that the students didn’t trust each other, despite the fact many of the students had been together since kindergarten and they were in a presumed safe space.

“That’s when I went exploring for how to build empathy in teenagers, and how to build buy-in from students at the high school level,” Chelsea said. “And that’s when I found Making Caring Common.”

“I can say ‘give me an example of where India was using her body language to show Owen that she was really listening,’ and they’ll answer ‘she was nodding or she smiled when you said something funny. Her body was turned towards him.’”

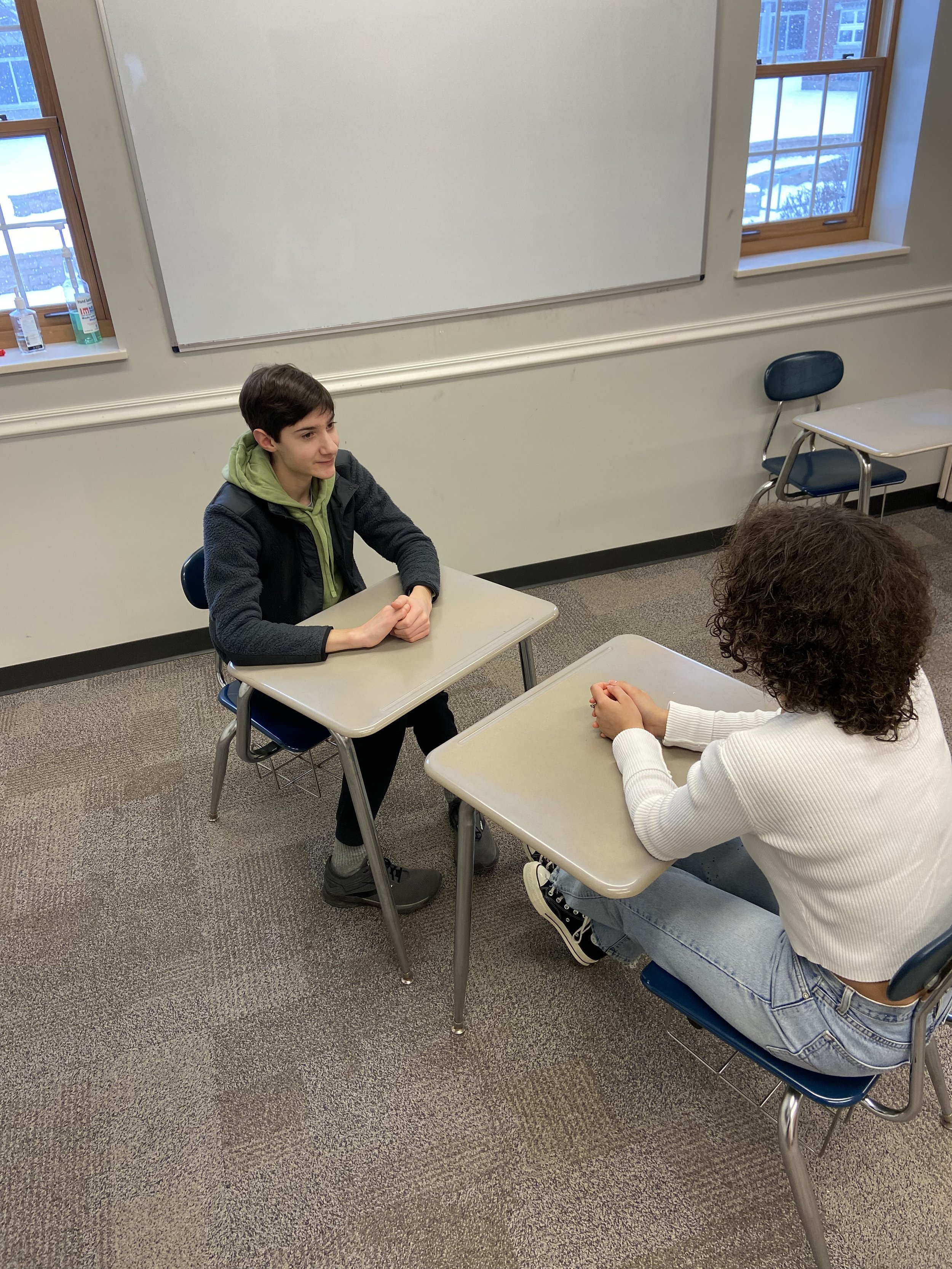

Chelsea started with our Listening Deeply Strategy for educators. It’s an in-depth lesson plan that allows students to practice being active, authentic listeners with a partner–listening to make the speaker feel heard without reciprocating in the conversation. In turn, it also raises the speakers’ comfort level with sharing and expressing their emotions.

Chelsea paired the students up and assigned a topic, like vegetarianism, and roles. For example, Partner A talks for two uninterrupted minutes, then Partner B engages in dialogue for one to two minutes. Then, they switch roles.

“Now we've been doing it so much, they know when they sit down there's going to be a topic. I pair them up differently every time and they know what the expectation is,” Chelsea says.

Understanding the roles and expectations has allowed the students to focus, spend less time in the practice itself, and more time learning what it means to be an active listener.

“I can say ‘give me an example of where India was using her body language to show Owen that she was really listening,’ and they'll answer ‘she was nodding or she smiled when you said something funny. Her body was turned towards him,” Chelsea says. “Now it's easy for them to come up with these things and notice them.”

Now that they have active listening down, Chelsea has been able to spend more time focusing on empathy and how skills that her students learn in seminar can transfer into other classrooms, and the community. Chelsea also incorporated our daily check-in survey and our Circle of Concern resources to help students expand their empathy.

“We had some interesting conversations about things like ‘how am I going to change the way I act to the cashier at Target?’,” Chelsea explains. “[There’s a difference] between saying ‘hi, thank you,’ and saying ‘I really like your scarf.’ Little comments like that can make such a difference for somebody.”

The results over time have been exactly what Chelsea had hoped for. Students who didn’t take lessons seriously at first have now bought into not just Chelsea’s seminar, but also their core classes like English and History. Chelsea has heard from her fellow teachers that students who have taken her seminar are more focused, more participatory, and better listeners. They’ve also become more open to sharing in the class survey – students who used to check in with one-word answers are now taking the time to share more – in and outside of class.

“Now I have kids waving through my window all the time wanting to just check in,” Chelsea laughs.

“...if you ask any teacher, they’re going to say the most important thing that they hope their kids take away from the work that they do is how to be a good person in this world. So I’ll be holding them accountable for that, even when I’m not teaching them.””

Chelsea’s experience isn’t unique, explains MCC’s Senior Project Manager of our Caring Schools Network Glenn Manning. The resources Chelsea used in her classroom are just a fraction of the resources he regularly uses with the dozens of schools who are formally part of the Caring Schools Network (CSN).

“When schools, students, and families work together to create more caring and just communities, we see decreases in nastiness, bigotry, harassment, and other problem behaviors,” says Glenn Manning, Senior Project Manager for the CSN. “We also see increases in students’ academic success, in their social and emotional skills, and in ethical capacities, such as the ability to listen deeply to and care for those who are different from them.”

Chelsea agrees that her focus on empathy with students is important for the classroom, but that she hopes it goes beyond that, too.

“I think especially in high school, there are a lot of reasons to be very self-focused,” Chelsea says. “But if you ask any teacher, they're going to say the most important thing that they hope their kids take away from the work that they do is how to be a good person in this world. So I'll be holding them accountable for that, even when I'm not teaching them.”

Posted by Jamie Farnsworth Finn, Digital Strategist